|

| you are currently viewing: {Location Field} |

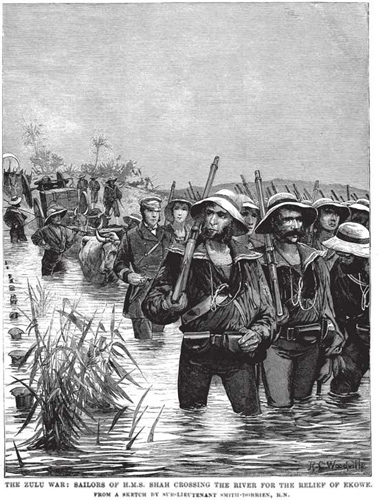

The Siege of EshoweBy Dawn Grant, 2009Of all the events of the Anglo-Zulu War, the siege of Eshowe tends to be the most overlooked. As a military campaign it could be termed a non-event, achieving little but the loss of officers and men yet it stands out as an example of British tenacity and ingenuity. Of course, it was never Lord Chelmsford’s intention that the First Column should become besieged. The Coastal Column was part of the General’s plan for the invasion of Zululand, one of five invasion forces that amassed on the Zululand border while awaiting the expiration of the ultimatum given to the Zulu king. The Coastal Column was commanded by Colonel Charles Knight Pearson of the 3rd Regiment (‘The Buffs’) and was comprised of:

The column began crossing the swollen Tugela River on the 12th of January, the crossing taking two days to complete, after which a fort was constructed on the Zululand side and named Fort Pearson. On the 18th January, the column set off into Zululand, making steady progress until the 21st of January, when the forces were camped within 4 miles south of the Inyezane River. On the next morning, the 22nd January, as a contingent of the NNC, led by Lieutenant Hart, pursued a handful of Zulu warriors, the column was attacked. The Zulu army had the advantage, attacking the column from an elevated knoll but the attack was repulsed, with Colonel Pearson making use of the Gatling gun and the artillery to counter-attack and drive off the Zulu army. Colonel Pearson lost 10 men and 16 wounded, while it is estimated that the Zulu lost 350 men. This engagement was the only known incident during the Anglo-Zulu War of a concerted Zulu attack on a British column whilst on the march. Colonel Pearson continued with the invasion, reaching Eshowe on the 23rd of January, while the last of the column came in on the following day, the 24th. The mission station at Eshowe was established in 1860 by the Norwegian Mission Society but had been abandoned in 1877 after a Christian convert was murdered on mission land. The only buildings left were a church, a school and the deserted dwelling house of the Norwegian missionary. As soon as they reached the station, the troops began to construct an entrenchment around the buildings and on the 25th, Pearson ordered a convoy of empty wagons to return to the Lower Drift escorted by two companies of the Buffs and the 99th.

On 27th January, Colonel Pearson received a vague telegram from Lord Chelmsford, stating that Pearson should disregard any previous orders and decide whether it was best to retreat or stay at the entrenched position at Eshowe. Furthermore he should be aware that he may come under attack from the full force of the Zulu army. The telegram made no mention of the reversal at Isandlwana and left Pearson perplexed as to what to do. He held a council of war and a tentative decision to retreat was agreed upon when a returning convoy was seen in the distance, heading towards Eshowe, bringing with it fresh supplies. The decision to retreat was postponed. On the day, 28th, it was decided that those volunteers under the command of Major Barrow and the NNC should return to the Tugela as there was not enough room in the garrison for them and not enough food to feed them. On the 30th, an attempt was made to drive 1000 oxen back to the Tugela as forage was rapidly being depleted but the convoy was attacked by Zulu not far from Eshowe. About half the oxen were captured by the Zulu and the rest driven back to Eshowe by their escort. On 2nd February, two runners brought the news of the full extent of the disaster at Isandlwana, which, Colonel Pearson soon realised, ironically took place on the same day that the attack had been repulsed at Inyezane. Colonel Pearson announced the news at parade the next day and it was this news that convinced Colonel Pearson to remain at Eshowe, sure that his men would be overwhelmed by the Zulu force while making a retreat back to the Tugela River. He sent a request for reinforcements but his letters crossed with Lord Chelmsford’s who ordered him back to Tugela to concentrate the forces. Colonel Pearson, after consulting with his officers, sent out a letter to Lord Chelmsford on 11th February explaining that large numbers of Zulu has been seen between Eshowe and Tugela but that if Lord Chelmsford insisted on it, he would retreat as ordered. No reply was received and the encampment acknowledged that it was now cut off from the main force on the Natal side of the Tugela River and under siege. Captain Wynne (Royal Engineers) oversaw the further fortifications of the entrenchments already in place. What had started as merely an earth entrenchment to protect supplies became a fully fortified position. The whole fort was surrounded by a ditch 7 feet deep and 13 feet wide, with earthen defences six feet high. A drawbridge was constructed at the main west gate and a smaller one at the northeast corner. There were firing platforms for the 7-pounders in the southwest and northwest corners, protected by sandbags. The church bell was removed and placed in the centre of the fort to sound the alarm, when needed. The troops settled in for the time being, not knowing for how long they would remain. The men rapidly lost weight as the limited rations dwindled away. They suffered as the weather changed for they were not allowed to erect tents as this would hamper a response to an attack. Instead they had to sleep under the wagons so that, when it rained, they would get wet which ultimately resulted in sickness and disease. In spite of Colonel Pearson’s best intentions to maintain a high level of sanitation, the confined conditions meant that disease began to spread. The first officer to die from fever and diarrhea was Capt HJN Williams of the Buffs who died on 12 March. Many more were to follow. The troops also suffered from lack of news but this was amended with the erection of a crude heliograph used to transmit messages using Morse code to the post at the Tugela. Captain Beddoes of the Natal Native Pioneers constructed the apparatus using a pivoted mirror, fixed to the end of a barrel and he engineered a sighting system by using wire directed by rods. As long as the sun shone, communications could be maintained with the fort at Tugela. Although Zulu could be seen all around the fort and there were frequent skirmishes, the Zulu army did not attempt to attack the garrison. Perhaps their experience at Rorkes Drift had dissuaded them from attacking a fortified post. On 29th March, Colonel Pearson received a welcome message from Lord Chelmsford that 4000 men would be coming to relieve the besieged fort. By now food supplies were extremely low and death by disease had claimed many men. On 30th March, the relief column could be seen through a telescope from Eshowe and excitement began to build. On the night of 1 April, the campfires of the relief column could be clearly seen and Colonel Pearson prepared a force to leave Eshowe and meet up with the column. However, just as the NNC was preparing to march out on the morning of 2nd April, shots were heard by the night picquets who were still on duty - the relief column was under attack; the battle of Gingindlovu had begun. From their elevated position, the men in Eshowe could observe the battle and ultimately the victory. In fact, it was Colonel Pearson who informed Chelmsford of the outcome as the General had no clear line of sight from his position. The column remained entrenched at Gingindlovu overnight and left at 7.30am on 3rd April while Colonel Pearson set out from Eshowe with about 500 troops. About four and half miles from camp, Colonel Pearson and Lord Chelmsford met and there was much handshaking in the Victorian way. The two men then rode together towards Eshowe while the Colonel filled in the General on the events over the past 3 months. The first person to arrive in Eshowe was a civilian – Mr Norris-Newman, the correspondent from The Standard, while the mounted troops led my Major Barrow arrived an hour later. The rest of the relief column took most of the day to arrive and it was about midnight that the 91st Highlanders marched in to the sound of bagpipes. The besieged men were delighted to see the relief column for the siege had taken its toll on them with three officers and twenty-five men dead and most of the remaining men sick with dysentery. The evacuation began on 4th April. Pearson’s men left first with as much of the meagre supplies that could be fitted on the wagons, with the men of Chelmsford’s relieving Column leaving on the 5th. The deserted post was soon occupied by the Zulu who set the buildings alight, but they, too, left the site once they had gleaned all that they could from the few items left behind, leaving the former mission site again abandoned. The column crossed the Tugela River on 7th April where the besieged officers and men found old friends and caught up with news. Unfortunately Captain Wynne, the architect of the defences of Eshowe, died as a result of disease on 19th April. The siege had lasted 72 days and had tested the resourcefulness of the British troops. In all respects the besieged garrison had held its own but had needed to be relieved by a stronger force. Now with the force of the Coastal Column now extricated from its position in Eshowe, Lord Chelmsford was able to turn his attention back to his initial objective: the invasion of Zululand. |