|

|

Horror at the Devil’s Pass

The Battle of Hlobane, 28th March, 1879

John Young

By Wednesday, 22nd January, 1879 the plans for the British invasion of Zululand lay in ruins on the blood-soaked battlefield of Isandlwana. It had been the strategy of Lieutenant-General Lord Chelmsford to assault the Zulu capital of Ulundi in a three-pronged attack carried out by No.’s 1, 3 and 4 Columns, supported by the reserve Columns No.’s 2 and 5, and destroy the power of King Cetshwayo kaMpande in one pitched battle. Scarcely eleven days after the commencement of the invasion, elements of No.’s 2 and 3 Columns were outmanoeuvred and massacred at Isandlwana - over one thousand, three hundred British and Colonial corpses littered the field. A like number of Zulus gave their lives in defence of their homeland.

On the same day, No.3 Column under the command of Colonel Charles Knight Pearson, of the 3rd (East Kent) Regiment of Foot, “The Buffs”, defeated a Zulu impi at the battle of Nyezane on the Indian Ocean coast of Zululand. Pearson advanced to his first objective, the abandoned mission station at Eshowe, which he fortified. On 28th January, Pearson received Chelmsford’s despatch concerning the Isandlwana massacre. Pearson’s instructions were to act on his own ingenuity, and, following an officers’ conference, it was decided to defend Eshowe against whatever forces the Zulu might pit against them - and thus began the siege of Eshowe.

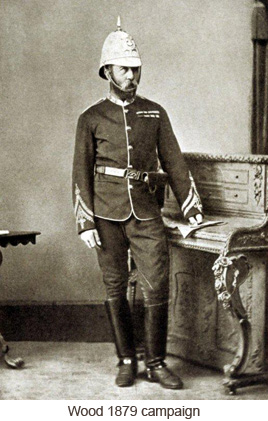

With two columns effectively destroyed and another besieged, Chelmsford looked to the only intact forces at his disposal - No.4 Column, under the command of Brevet Colonel Henry Evelyn Wood, V.C., of the 90th (Perthshire Volunteers) Light Infantry and No.5 Column, commanded by Colonel Hugh Rowlands, V.C., formerly of the 34th (Cumberlandshire) Regiment of Foot. Chelmsford directed that most of Rowland’s command be absorbed into No. 4 Column. Wood's command was further reinforced by the arrival of the Edendale Troop of the Natal Native Horse and the 1st Squadron, Mounted Infantry, transferred from the shattered remains of No.’s 2 and 3 Columns respectively.

Wood’s Column became a thorn in the side of the Zulu forces in north-west Zululand, operating from its encampment of Khambula, making effective raids into enemy territory.

The forces which ranged against Wood were a mixed band comprising Zulu; abaQulusi (a subjected indigenous people who had sworn allegiance to King Cetshwayo.); and disaffected amaSwazi, the followers of Prince Mbilini waMswati, “The Swazi Pretender,” who had in turn pledged their fidelity to King Cetshwayo. This hotchpotch banded together still presented a force to be reckoned with and, once organised, they commenced counter-raiding, striking terror into the civilian population - black and white - along the Zulu/Transvaal border.

Prince Mbilini’s greatest success in the region was the attack on 12th March, 1879, on the encamped wagon convoy under the escort of Captain David Moriarty and a company-strength detachment of the 80th (Staffordshire Volunteers) Regiment of Foot, on the Ntombe River. Moriarty and sixty of his men perished along with a civilian surgeon, three European wagon conductors and fourteen African voorloopers. Mbilini pillaged the convoy's supplies, and made off prior to the arrival of British reinforcements. Mbilini proudly boasted of his victory to King Cetshwayo, who he also begged for reinforcements from Ulundi, to supplement his own forces.

Lord Chelmsford desperately needed a victory to silence his armchair critics in Britain. Reinforcements arrived in the wake of the Isandlwana reverse, and with these troops he turned his attention to the relief of Pearson's besieged column at Eshowe. To coincide with this relief operation Chelmsford ordered Wood to create a diversion in his theatre of operations on 28th March, in the hope that it would draw off some of the Zulu forces besieging Eshowe.

Wood decided on an assault on the enemy stronghold on the plateau of Hlobane Mountain. In the meantime, on 24th March, King Cetshwayo, recognising that Wood had proved to be a greater adversary than any other British field-commander, answered Mbilini's pleas and despatched the main Zulu army under the command of Mnyamana kaNgqengelele, with Ntshingwayo kaMahole - the victor of Isandlwana - as his field-commander.

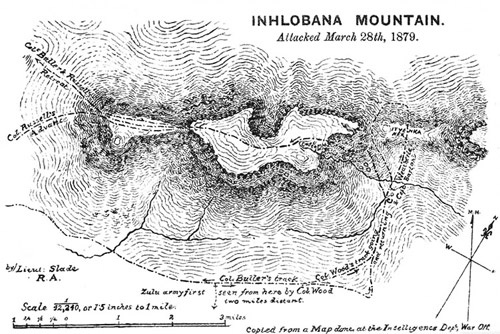

Wood devised a pincher assault on Hlobane. From the east this would be under the command of Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel Redvers Henry Buller, of the 60th Rifles (King’s Royal Rifle Corps), and that from the west would be under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel (local rank) John Cecil Russell, 12th (The Prince of Wales’s Royal) Lancers.

At about 9 a.m. on Thursday, 27th March, Buller’s force, which was composed of a Royal Artillery rocket party, some four hundred irregular cavalrymen drawn from the following units: the Burgher Force; the Frontier Light Horse; the Transvaal Rangers; the Border Lancers and Baker’s Horse. Also accompanying the eastern assault force were 277 officers and men of the 2nd. Battalion of Wood’s Irregulars, an African levy officered by white officers. Russell's party left some three hours later, it comprised of another rocket party, the 1st Squadron, Mounted Infantry, numbering just over eighty men, the Edendale Troop of the Natal Native Horse - which had acquitted itself so well at the debacle at Isandlwana - of some seventy men. The Kaffrarian Vanguard - forty officers and men. The 1st Battalion of Wood’s Irregulars, numbering some 240 officers and other ranks. Also accompanying this force were some 200 disaffected Zulus, the adherents of King Cetshwayo's step-brother, Prince Hamu kaNzibe. Wood left Khambula with a small personal staff and escort, which included Prince Mthonga kaMpande, a younger brother of King Cetshwayo, who had sought refuge in the British Colony of Natal in 1865 fearing that his own brother might order his death; now was the chance for him to repay the British for their hospitality.

The two attacking parties made their way unchallenged towards their respective objectives, and bivouacked. Fires on Hlobane betrayed the enemy’s position. Wood received intelligence that the main Zulu army were heading in his direction from the Royal ikhanda at Ulundi, and he duly placed scouts to watch the possible approaches.

Before resting that night, Wood held lengthy discussions with two men who knew the objective well; Petrus Lafrus Uys, the veteran Boer commando leader who now commanded the Burgher Force, and Captain Charles Potter, of the 2nd. Battalion of Wood's Irregulars, who had traded in the region before the war. Their discussions concluded, Uys spoke prophetically to Wood, “...if you are killed I will take care of your children, and if I am killed you do the same for mine.”

Buller too was fearful; fearful of discovery and moved his force twice to avoid being found by Zulu scouts. At 3 a.m. on Friday, 28th March, Buller's force commenced their ascent of the difficult slope. To add to their problems a heavy storm broke over them. Flashes of lightning illuminated the ascending force; the rain turned their route into a sodden path, hindering the climb. The storm abated as quickly as it had started and the clambering troops picked their way up through the boulder-strewn track.

Dawn broke and a new horror became apparent. The Zulu were behind prepared barricades and concealed within caves that riddled the mountain, awaiting the assault. From behind their positions, the Zulus opened fire on the scaling troops. Two officers of the Frontier Light Horse, Lieutenants Otto von Stietencron and George Williams, fell dead, two troopers also fell to the fire.

Wood and his escort rode to the sound of the firing. Just below the summit of the mountain plateau they chanced upon Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Augustus Weatherley and his Border Lancers. Weatherley’s unit should have been with Buller, but during the storm they had become separated and now lagged behind. Wood spied a Zulu rifleman level his gun in his direction and he expressed his contempt of the Zulu marksmanship. The Zulu fired, and his bullet found its mark, shattering the spine of Mr. Llewelyn Lloyd, Wood's Political Assistant and his interpreter, who was at Wood's side. Wood attempted to lift the mortally wounded man, but stumbled under the weight. Captain the Honourable Ronald Campbell, Coldstream Guards, Wood’s chief staff officer, came to his aid and carried the dying Lloyd out of the line of fire. Again a Zulu fired at Wood, killing his led mount. The horse fell against Wood, and caused him to stumble.

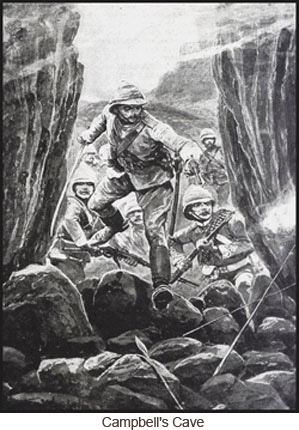

A gasp went up from his men, fearing their commander wounded. Wood shouted a reassurance that he was not hit, and picking himself up, he made his way downhill to the troops’ position. Angered at being pinned-down, Wood ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Weatherley to assault the position from where the fire was coming. Weatherley in turn, addressed his men, ordering them forward, but only Lieutenant J. Pool and Sub-Lieutenant H.W. Parminter responded to the command. The remainder of the Border Horse refused to assault the position, saying that it was unassailable. Captain Campbell was horrified; this was tantamount to mutiny - if not cowardice.

Campbell was of ennobled birth, the son of the 2nd Earl Cawdor. Such behaviour was unheard of within the class to which he belonged. Uttering his contempt of the fainthearted volunteers, he sprang forward towards the foe, supported by Second-Lieutenant Henry Lysons, 90th Light Infantry and four mounted infantrymen of Wood's personal escort, also drawn from the 90th. The small party advanced in a determined manner, clambering over boulders and through crevices, which led to the Zulu position. The path was so narrow that the advance could only be made in single file. Campbell gained the mouth of the cave first, only to be shot in the head at point-blank. Undeterred, Lysons and Private Edmund Fowler carried the position, forcing the Zulus to withdraw into a series of subterranean passages and, with Lysons and Fowler in pursuit, they killed all those who offered resistance, and put the others to flight.

With Lysons covering the cave mouth, Campbell's body was brought down and placed alongside Lloyd, who had succumbed to his wound. Fearful of the bodies being mutilated, Wood decided to bury them on the field. Being the son of a clergyman, he wished to conduct a proper burial service, only to realise that his service book was still in the wallets of his saddle on his dead mount. He ordered his bugler, Alexander Walkinshaw, to recover the prayer book. Walkinshaw, whom Wood described as “one of the bravest men in the Army,” calmly strode up, under heavy fire and recovered not only the prayer book but also the entire saddle.

Wood had the two bodies removed some three hundred yards downhill, to where the soil was less rocky and the Zulus of Wood’s escort dug the grave with their spears, under the watchful eye of Prince Mthonga. Their task completed, Wood committed the two bodies to the ground, reading an abridged version of the burial service from a prayer book which belonged to Captain Campbell’s wife, who was the daughter of the Bishop of Rochester, Kent.

Buller’s force was, in the meantime, quelling any resistance being offered and commenced sweeping along the plateau, capturing cattle as booty. Weatherley’s Border Lancers found their courage, perhaps encouraged by the deeds of a few, and recommenced their ascent.

On the plateau, Buller met with Captain (local rank) Edward Browne, of the 1st Battalion, 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot, who had with him some twenty men of the mounted infantry from Russell’s party. They had scaled the rugged path connecting the Ntendeka and Hlobane. Browne informed Buller that Russell had concluded that it was impossible to ascend the steep escarpment with his entire command. On hearing this intelligence, Buller ordered Captain Robert Barton, Coldstream Guards, commanding the Frontier Light Horse, to take some thirty men of the corps to bury the bodies of their earlier fallen comrades. Barton was also charged with the task of locating the whereabouts of Weatherley and his men. Minutes after Barton’s departure Buller stared aghast at the sight that confronted him on the plain below Hlobane. Approaching from the south-east was a Zulu impi numbering in the region of 20,000 men.

Wood’s attention had been drawn to the advancing impi by the frantic shouts of his Zulu escort. Lloyd had been the only Zulu linguist in Wood’s party and he was dead, but there was no need of an interpreter to convey their urgent words of warning.

Buller despatched a note to Barton ‘return by the right of the mountain’, a message which he had hoped would convey to Barton that he should withdraw in the direction of Khambula. Barton had by now located Weatherley, who fell in with Barton. The message reached Barton but sadly, it was misconstrued, and Barton unwittingly led the pitifully small force straight into the path of the Zulu impi. The mounted volunteers were swallowed up by the Zulu host, and swiftly overwhelmed. Weatherley died apparently hand-in-hand with his fifteen-year old son, who had joined his father’s corps as a sub-lieutenant. Only a handful evaded the slaughter. Captain Barton saw Lieutenant Pool had been unhorsed and rode to his rescue. Taking him upon his mount he fought his way clear of the melee, pursued by a number of Zulus. For some seven miles, Barton managed to outdistance the warriors, but his horse floundered under the weight of the two men and the Zulus closed in on their prey and killed the two officers.

In a handwritten report Buller blamed himself for the tragic loss of sustained as a consequence of his misinterpreted dispatch; however, another hand (Wood’s?) has struck out this self-accusation, censoring the transcript which admits to error.

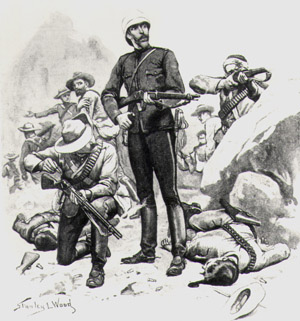

The Zulu defenders on the summit, seeing that reinforcements were at hand, renewed their harassment of Buller’s force. Abandoning the livestock the force had taken as a prize, Buller ordered his African levies to descend first. The levies gingerly scrambled down through the boulders and took to their heels. Some one hundred of the levies were outpaced by the fleet-footed young Zulu warriors and perished. The mounted men found the descent less easy; slowly they picked their path down the steep slope, leading their horses, threatened on all sides by Zulus. This pass between the two mountains would acquire a name, which reflects the horror of the descent - The Devil’s Pass.

Buller had expected to have received some support from Russell and his western party, but due to another misconstrued dispatch (this one from Wood) Russell had evacuated his position. The only assistance that Buller's men received came from Browne and his small body of mounted infantry.

In the turmoil of the retreat, Buller banded together a staunch rearguard, and contested the overwhelming Zulu numbers, which permitted the escape of a great number of his men. Soon the weight of the numbers of Zulu pressing the rearguard forced Buller to abandon his position, and fight gave way to flight. The Zulus captured men, hurling them to their deaths off of the mountain. Others rather than share this fate turned their own weapons on themselves. In the chaos several men lost their mounts. Buller rode back time and again and snatched men from the very jaws of death. His fearless example was followed by Browne, and by Major William Knox Leet, of the 1st Battalion, 13th (Prince Albert’s Own Somersetshire) Light Infantry.

Commandant Uys, who had earlier implored Wood to take care of his children, turned and saw one of his sons surrounded by Zulus. He rode back in the mass of warriors and extricated his son from his predicament, only to be speared in the back by a Zulu who leapt onto his horse before he could make good his own escape.

With further resistance futile, the British and Colonial forces abandoned the field, it was about 12 noon. Seventeen officers and eighty-two white troops were dead, as were some one hundred African levies. Of the Zulu, there is no accurate number of losses known.

Four Victoria Crosses were eventually awarded for the action at Hlobane. The recipients were Buller, Leet, Lysons and Fowler. Five Distinguished Conduct Medals were also awarded, including one to Wood’s redoubtable Bugler Walkinshaw.

As a postscript to honours and medals awarded for Hlobane, there was at least one other officer recommended for the Victoria Cross, who is worthy of mention; Veterinary Surgeon 1st Class Francis Duck, of the Army Veterinary Corps. Duck was recommended for the Victoria Cross by Buller for his gallantry in action during the retreat towards the Devil’s Pass when he took a dead man’s rifle he volunteered his services with the rearguard and rendered excellent service at a most critical moment, only to have his name struck out by the Commander-in-Chief on the grounds ‘…that he had no right to be there.’

|